Becoming an Abundance Democrat

No longer a New Deal Democrat, but an Abundance Democrat

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance was released a few days ago. The long-awaited book from two of our generation’s best political thinkers came at a time when our path forward is highly uncertain. It placed a lens for understanding our history beyond the left or right wing. It explains the basic human impulses that have shaped our politics since the post-war period. Klein and Thompson hone in on the concept of “Scarcity” as a choice that shaped politics, culture, and society. All sides of the political spectrum yearn to return to the past. Right-wingers for cultural hegemony, nuclear family, and the dream of economic mobility. Left-wingers for the strength of unions, the expansion of the welfare state, and the dream of economic mobility. Therein lies the correlation: economic mobility and opportunity. The rationale behind our reverence for the past lies in basic economics. People yearn for more. Moreover, they believe the past was the time of more, and thus yearn for the past. They yearn for a past where housing was affordable, jobs were plentiful, and when family values and community were central to our way of life. Whether real or imagined, this past is what the overwhelming majority of society yearns for. The answer lies in more, whether it be more job security, opportunity, healthcare, mobility, or whatever. As Econ 101 taught us, the principle of economics is balancing infinite wants in a world of finite resources. Abundance, as defined by the opening paragraph, understands that scarcity is a choice—the result of which is the defining influence on our politics and history leading to this moment.

Scarcity Incarnate

We live under the second Trump administration, watching passively as Trump and Musk take a chainsaw to the Federal Government. At the same time, Democrats face a crossroads of the party's identity and agenda. Despite the unpopularity and controversy of the Trump administration in the first term, he managed to return to the White House and secure a popular vote victory. Something about Trump and his movement is working here. Rather, something about it is appealing to Americans. What is that thing? Democrats and liberal thinkers alike have proselytized what that ‘thing’ that Trump channels. In 2016, the consensus was white working-class grievances over deindustrialization and the hollowing out of the American heartland. Protectionists and, more so, populists believed the way back was promising pro-union, pro-working class, pro-industrial, and antitrust policies to win the voters back. Strategists thought the promise of opening the factories again and restoring manufacturing would win the voters back—it didn’t. Bailing out union pensions, pro-union NLRB appointments, and the former President of the United States walking a picket line didn’t swing the unions. Antitrust enforcement from the FTC’s Lina Khan battering Big Tech didn’t swing voters; attacking Amazon, Google, and Facebook didn’t. Silicon Valley and the traditionally liberal donors and bloc swung to Trump and the GOP this cycle, citing the aggressive stance taken by the Biden administration.

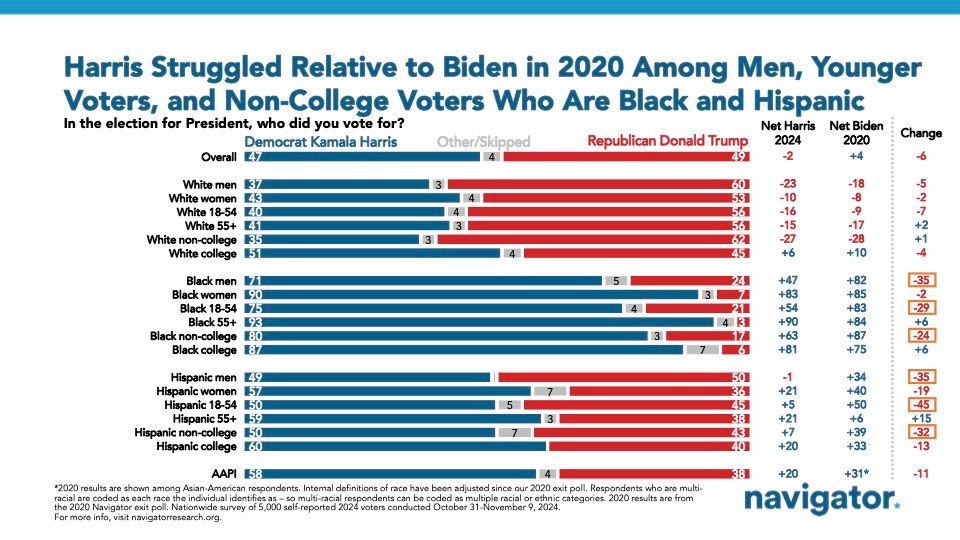

Liberal stances on immigration would hold the emerging Latino majorities, said the activist groups. After all, Trump has openly lambasted Mexican immigrants and employed a torrent of racists in his administration. That didn’t work either. Fourteen million immigrants entered the country over 4 years. Despite the economic benefits in the aggregate, immigration backlash became one of the most perceptible political issues of the 2024 election. Race-consciousness policymaking would hold Black and Asian voters. After all, activists told us that relaxing policing and closing the prisons would benefit these communities. Instead, we have a majority consensus that liberal public safety and governance approaches are nothing more than a failed experiment. The most liberal cities and states have become the butt of the joke, and the voter blocs, as mentioned earlier, again swung towards Trump. Why? Chalking these massive swings to anti-incumbency vitriol, discontent about foreign wars, or culture war issues is lazy thinking. To some extent, ALL of these issues are part of the problem, but not THE problem. What is the core theme here when voters consistently rank the economy and inflation as their number 1 issue?

Scarcity. Scarcity is the issue. Scarcity is the lack of housing, healthcare, jobs, and more opportunities. Scarcity is the cost-of-living issue. Scarcity is the inflation issue. In a society of general abundance, we overlook the scarcity of simple goods; we have phones, drones, and gadgets galore, but we lack sufficient roofs to place overheads or doctors to care for us when we are sick. Rather than papering over these issues by blaming Immigrants for the lack thereof or blaming corporate greed, we must understand that the underlying demand for solutions is addressing the scarcity of what we need.

Abundance explains that the scarcity of the things we need is an artificial scarcity—things don’t need to be this way. We can have more. We did it before; we can do it again.

Populism and Scarcity

American Populism of the 21st century originates from the belief in scarcity. Populism from both sides of the spectrum, whether Trumpism or Bernieism, coalesce around the simple truth of populism: in-group vs. outgroup, us vs. them, the average citizen vs. the elites, and the masses vs. the powerful. Populists such as Trump and Sanders alike channeled mass frustration and anger into their ingroup vs outgroup rhetoric, providing seductively and reductively simple plans for addressing the frustration most, if not all, Americans feel. By mobilizing the masses of “working-class Americans/silent majority” to “provide Medicare-for-all/build the wall,” we can “Make America Great Again/Feel the Bern.” It's weird how the slogans seem to line up. I’ll take it one step further; both sides criticized NAFTA and Free Trade Agreements (Economic Nationalism), both criticized the ‘establishment’ (liberal elites somehow came from both campaigns), both targeted economic insecurities of working/middle-class voters (tax cuts from Trump or taxes on billions for expanding the welfare state). In discussing the same issues, both populists, left and right, provided a simple solution to problems that require a far greater sense of nuance and complexity to address adequately. No false equivalency should be drawn about the policies laid out. Still, the underlying rationale of punishing the outgroup for benefiting the ingroup and the reductive populist messaging that avoids tangible solutions and instead stokes the frustrations and anger at the establishment is the corollary.

Furthermore, the reductive populism is ABUNDANTLY clear (see what I did there?) when considering each side's consistently lazy and incoherent policy proposals. Whether it be Trumpism’s insistence on massive tariffs to pay for the elimination of income tax or the constant repetition of the wildly misleading to outright false statistic that 60% of Americans live paycheck, both fall for the seductively simplistic solutions to our problems. This lazy reduction of complexity is endemic to our problems, but rather than getting creative—thinking and innovating our way out of problems- we choose to play the blame game. Outcomes that unravel the issues are the solution. Campaign rhetoric be damned—misleading and repeating falsehoods is NOT the solution. Populist and left-leaning Sander’s acolytes continue to parrot that the emotion and energy of the issue is far more critical than the correctness—which, although this may be true, we are engaging in a devil's bargain. Do we choose to ride the tiger in the hopes of winning? What happens when the tiger (or, as my favorite metaphor goes) the leopard decides to eat our face? What happens if Sanders became the nominee, promising Medicare-for-all with a GOP House and Senate? What occurs when our simple promises become burdened by reality rather than hypotheticals? What happens when Trump’s tariffs and cuts to the Federal workforce don’t balance the budget and harm the economy—instead of beginning the ‘golden age’ of America?

Right, Left, & Center

The underlying theme of our political debates is the concept of scarcity. Whether real or imagined, we are debating over the core principle of scarcity. On the right, the underlying belief is that those unlike us, the boogeyman of the time, whether it be immigrants, lgbt people, people of color, or more, are taking what is yours (housing, jobs, etc.) The left believes that there is not enough of what people need but that the rich and powerful are to blame. The right believes there is not enough of what people need, but that immigrants and wokeness are to blame. By boiling down the central logic of both ideologies, there is scarcity or simply not enough of thing X, and if we punish outgroup B, there will be abundance for ingroup A. Go ahead and substitute any good or item that people NEED in their lives (healthcare, housing, jobs, etc.) and substitute any group that either side of the spectrum loathes (billionaires, corporations, immigrants, lgbt, etc.) The pattern should emerge clearly in understanding the debates. By framing our necessary political battles as a race to the bottom of who can be more populist—duking it out over scarcity views and culture war shenanigans, our politics' asinine, reductive, and unproductive debates become even more transparent—and all the more embarrassing. Something here has to change.

Abundance, as laid out by Klein and Thompson, is an outcome we should all aspire for. A society where medicine, housing, energy, and more are universally available? That’s a goal I can get behind. The authors purposely leave out specific plans and policy objectives for getting there, which is a purposeful decision. Assigning themselves to specific ideologies of corporate anti-trust, deregulation, or further government intervention hinders the discussion. The idea of strictly liberal, leftist, centrist, and right-wing solutions in the book is purposely absent. The goal outlined is the abundant society the authors envisioned. By leaving the roadmap to abundance ambiguous—we are free to create, innovate, and think our way out of our issues. The authors clarified that adhering to a strict ideology of punishing those unlike us, the ‘outgroups’ to benefit the in-groups, is a scarcity mindset. Instead, we must think about outcomes. Rather than considering if our actions fit into our individual viewpoint paradigm, Klein and Thompson dare the readers to focus on outcomes instead of process. If de-regulating housing produces more affordable homes for more people, is that not a noble goal? Is it nobler to dig a line in the sand and refuse de-regulation in religious adherences to anti-free market beliefs, even if the cost bares down on those we purport ourselves to be helping? Suppose de-regulating housing laws means housing is built and rents are coming down, is that outcome not better than maintaining our rigid belief of anti-corporation/anti-free-market thinking while our citizens live in tents under freeways?

The online vitriol for Abundance is made ABUNDANTLY clear by those who read and understood the book versus those who parrot the hardline stances of online mutuals. In reading the book, we are to understand that there lies an optimistic future achievable by the innate greatness and talent within each and every individual. The lack of specifics is meant to leave the readers engaged with their idea of solutions—driving innovation, driving discussion, and driving progress. The core concept of scarcity is meant to drive readers to think about outcome-oriented solutions, drive readers to think bigger, dare readers to dream bigger, and promote the Abundance laid out in the opening pages. We will get nowhere if we spend our time bickering over X or Y as simple solutions to our problems—in driving progress, talking about these issues is the first step to solving them.